Ambient dystopia

What happens when vibes replace vision?

Welcome to Mutant Futures: a newsletter about culture, futurism and strategy.

In this edition, I unpack our cultural relationship with dystopias.

Let’s get into it 🔬

The word ‘dystopian’ seems to be unavoidable these days—on and off Substack. I can think of a bunch of reasons for this:

Trump’s election victory last November, which also prompted a surge in US book sales for dystopian faves like The Handmaid’s Tale.

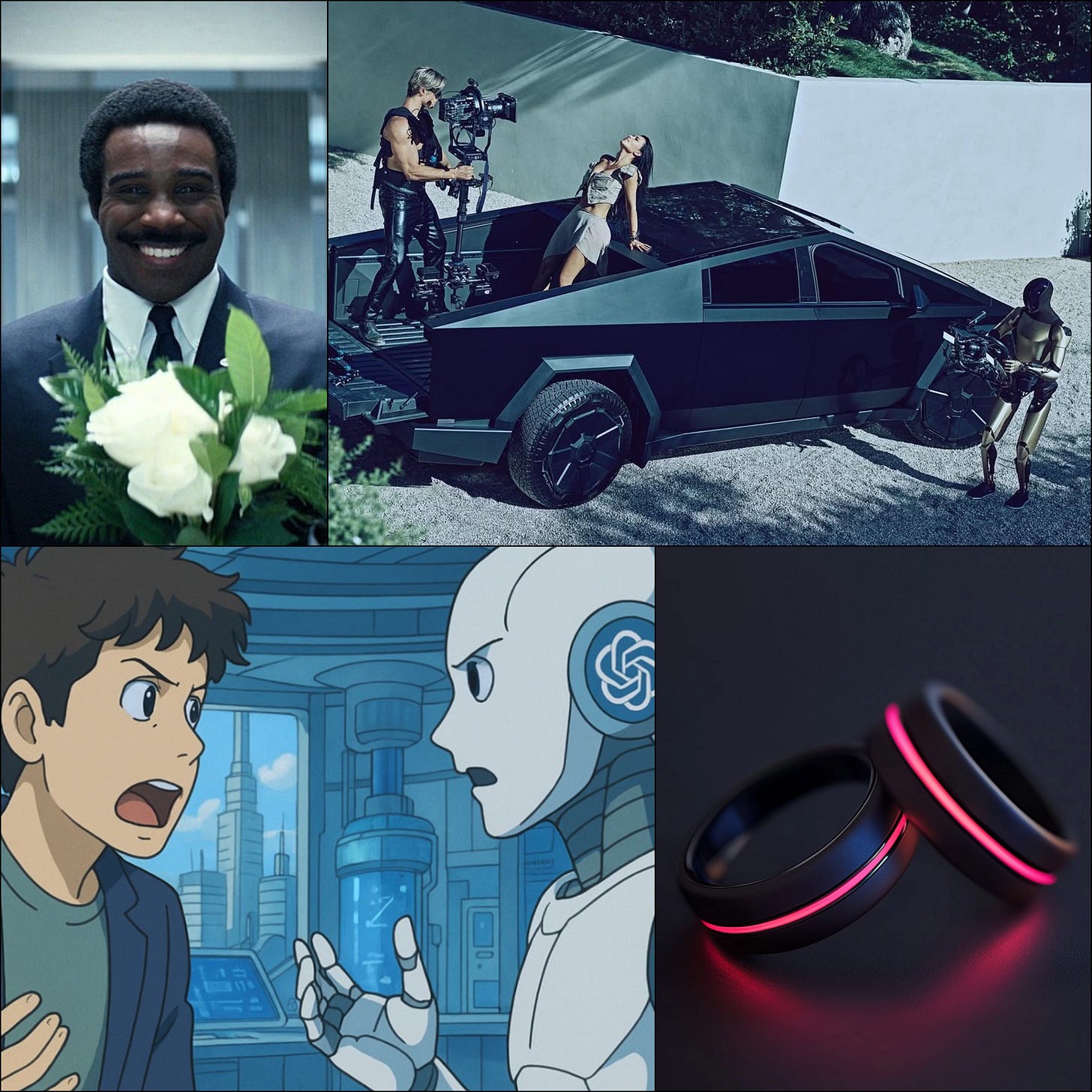

Tech billionaires have gone full rogue, in a way that brings sci-fi to mind.1

AI has disruptively occupied the public conversation, threatening our intellects, artistry, careers and climate goals.

Humanoid robots walking to synthwave music.

Recent film & TV hits with bleak storytelling and stylish visuals have captured our imagination (Fallout, The Substance, Severance, to name a few).

Dark and gothic aesthetics are having a moment in fashion and wider culture.

Climate disasters are ramping up, while some influencers film them for content.

The signals are talking, and they’re saying ‘dystopia is just a vibe now’. What used to be the language of decay is now a design language. A mood. A look. A value proposition. For brands, for entertainment, for cultural capital.

The idea for this essay started from the following thought: in a world where bleak sci-fi and real life resemble each other more than ever, should we ban dystopian stories? This provocation really got me going. Maybe let’s not outright ban things, as that would be quite ironic. But the question still stands: when our lives are dominated by dystopian narratives, should we de-prioritise stories that depict bleak and undesirable futures?

Before we entertain that debate, let’s unpack why dystopia feels so sticky, psychologically and culturally.

We’re wired for dystopian thinking

Let’s talk about negativity bias for a second. Believe it or not, humans have evolved to prioritise the negative. Why? Because for our pre-historic ancestors, staying alive was hard work. So staying alert was do or die, quite literally. Not just alert to sabre-toothed tigers, but to anything and everything—a storm, a plague of insects, a tribal ambush. A sabre-toothed tiger trying to eat your baby, while a storm is breaking out and the shelter’s leaking and the tribe is pissed you ate the last berries? You name it. And so our brains are biased towards fear, risk and danger.

⏩ Now modern humans aren’t burdened by quite the same things, but we still over-index on the bad. It’s why we obsess over an uncomfortable interaction at an otherwise enjoyable event. It’s why we get nervous when we hear shouting in public. You get the idea. And negativity bias doesn’t just show up in our reactions, but also in our language. When things feel off or quietly threatening, we reach for words that help make sense of it. And lately, that label is often ‘dystopian’. It’s become a catch-all term for the darkly surreal moments we increasingly encounter in real life:

A dating app that selects your matches for you, with AI?

A company that films its employees every day for social media content?

A theme park that uses surge pricing to charge you more on sunny weekends?

Dystopian, dystopian, dystopian. And all true—number two used to be my actual employer 🤭

Here’s the thing: when a single word covers so many dysfunctional scenarios, it becomes a default label. And the more we label things ‘dystopian’, the more we risk saturating our thoughts with that state of dysfunction, to the point of numbness. It stops feeling like something to question, and starts feeling like the background noise of everyday life. Ambient. Documentary-maker Adam Curtis captured this phenomenon in HyperNormalisation (2016): during the final years of the Soviet Union, everyone (citizens, officials, even the media) knew the system was broken. But they kept participating because they couldn’t imagine an alternative system. Reality had become performative, and dysfunction was accepted as the everyday norm.

So it’s tempting to throw the word ‘dystopian’ out altogether, and to assume that dystopian stories are part of the problem. After all, by depicting these unsavoury worlds, aren’t we just encouraging the 1% with unsavoury agendas and the means to create those worlds?

Cyberpunk and its aestheticised corruption

The seduction of much dystopian storytelling is also its curse: aesthetics. Some dystopias present decay so nonchalantly, it stops feeling like a problem and starts feeling like atmosphere. The biggest perpetrator of this, arguably, is cyberpunk. A genre synonymous with cityscapes that actually exist in our world today: glassy high-rises showing billboards with neon ads, for omnipresent mega-corporations.

When the genre crystallised in the 80s and early 90s, cyberpunk was critical of the things it depicted: monopoly-chasing multinationals, increasing wealth inequality and technology intruding on our private lives. Pioneering novels like Neuromancer (by William Gibson, published 1984) and Snow Crash (Noel Stephenson, 1992) constructed worlds where power had shifted away from governments and into the hands of unaccountable tech elites. This commentary on corporate power was also alive in the cyberpunk films of the time, notably Blade Runner (1982).

As decades passed, the ‘punk’ aspect was eclipsed by the genre’s aesthetic appeal, which made it more marketable for entertainment. Whether it was TV (Altered Carbon), film (Blade Runner 2049) or video games (Cyberpunk 2077), today cyberpunk no longer serves as a movement, but as a moodboard. For Hollywood, streaming companies and so on.2 The nail in the coffin came from AI, which has accelerated this aesthetic flattening, as Gary Yong points out in The Neon Graveyard. Image generation models trained on cyberpunk imagery don’t understand context or critique. They understand the aesthetics only, rewarding what’s stylistically consistent and instantly recognisable. In doing so, they completely sever cyberpunk from its ideological roots.

Soft dystopias, with soft colour palettes

To add another layer to the discussion of aestheticisation, we need to talk about soft dystopias. The OG soft dystopia, Brave New World (Aldous Huxley, 1932), depicts a society controlled by consumerism and pleasure. The book highlights the dangers of collective complacency. Unlike dystopias that involve violence or apocalyptic conditions, this type of story explores systemic decay and oppression through psychological or emotional means.

A modern and popular example of this niche is Spike Jonze’s Her. It presents AI as an emotionally intelligent companion: charming, adaptive and deeply empathetic. This framing sidesteps classic fears of machine domination, inviting viewers to sympathise with the AI, blurring the line between tool and sentient being. The film presents its story with a warm, almost soothing aesthetic. Its inviting visual palette, with its vibrant colours and gentle light, creates a world that feels innocent, subtly masking the theme of loneliness at its core. While it ends on a reflective and human-centric note, the film renders its dysfunction beautiful and quietly normalised. At the time of release (2013), Her was read as a cautionary but understated tale about the tech-enabled outsourcing of relationships and empathy. But in today’s age, that’s no longer fiction. It stands as another example of how stylised visuals can seduce us into softening our attitudes about the underlying, problematic issues.

More substance, less style

At this point, the case against dystopian storytelling is well-founded. Why invite more of it? Speculative stories adopted by pop culture continue to lean heavily on style at the expense of substance and messaging. Why entertain more dystopia? Because not all dystopian stories are problematic, and because we need to champion more useful dystopias. When done right, these stories can act as warnings and scenario simulations to inspire real-life activism. To give a brief example from film, V for Vendetta (2005) provided both a symbol and philosophical input for protest movements like Occupy. These are dystopias that provoke agency over apathy.

I wanted to end this essay on a note of hope, as that’s why I decided to write this series—to talk about which futures centre hope. So I’d like to share with you some wisdom from the late great Octavia Butler. In her classic essay, A Few Rules for Predicting the Future, Butler reminds us that strange futures can act as a useful resource. She explains why dystopian world-building is important: to imagine systemic struggles that we can learn from. Her point is that speculative fiction isn’t about prophecy, it’s about diagnosis. It helps us question the status quo, and rethink our systems. A story that unsettles us might still be generous, if it helps us widen our thinking. The challenge is distinguishing between dystopias that darken our imagination and those that sharpen our vision in the dark.

This essay is part 1 of a two-part series. Read part 2 here.

Thank you for reading! 💜 If you haven’t subbed already…

Thanks for the reference, Philip! The language of dystopia definitely needs further interrogation like this .. and how do we get to utopia while not robbing its sex appeal? 👄🌱

Omg yes, love that you wrote about this! Used to think about this all the time in Berlin since it's basically a city inspired by dystopian sci-fi in many ways. I always wondered how much it came to be simply out of a lack of critical thinking - as you say: aesthetics first. Looking forward to the next one.