Welcome to Mutant Futures: a newsletter about culture, futurism and strategy.

In this edition, I talk about the stories that help us imagine better futures.

This essay is part 2 of a two-part series.

Let’s get into it 🔬

In 2025, the zeitgeist is seemingly saturated with dystopian narratives—that was the topic of my last essay. When dysfunction is all we can think of, our capacity for hope suffers too. And when progress feels like a fantasy, we struggle with anything remotely ‘utopian’. But what if I told you that romanticised world-building was overrated anyway?

Beyond the utopia-dystopia binary

In speculative fiction, the utopian/dystopian distinction is only half the story. Sometimes, the power of hope is best captured through worlds that are neither very peachy, nor very grim. Enter the ‘ambiguous utopia’. Coined by Ursula K. Le Guin in The Dispossessed (1974), it’s a world that’s functional in some ways and dysfunctional in others. The book focuses on two contrasting societies:

Urras, a planet defined by prosperity. Home to sprawling cities and academic prowess, but also deep inequality. It’s ruled by competing nation-states, each built on privilege and patriarchy. Ambition drives success, but getting a seat at the table depends on your class, gender and connections.

Annares, an anarchist moon colony. There are no rulers, no property and no hierarchy. Here, everything is shared and ego takes a back seat. But over time, the system has a side-effect: psychological and cultural constraint. How? By stigmatising those who show too much individual thought. All in the name of collective harmony.

The story follows Shevek, a gifted physicist who starts to feel boxed in on Annares. He’s working on a theory that could make instantaneous communication across vast distances possible, faster than light. But his unconventional thinking is not encouraged, and his research isn’t given the space it needs. The pressure to be conformist leaves him frustrated. Hoping to find a better environment to develop his work, he travels to Urras. At first, it’s everything Annares isn’t. He’s celebrated, well-funded and surrounded by top scholars. But this comes with its own price: his work is co-opted to serve political agendas, and he’s caught in the middle of it all.

So it turns out that neither society is more preferable than the other; both involve tensions and trade-offs. The message? Utopia is not a fixed state but an ongoing, dynamic process. Utopia is a verb. What matters is pushing for something different, doing the work to change the system rather than just escaping it.

The quiet power of protopias

Thinking about stories on a spectrum, not as a binary, means that we can hold space for the messiness of progress. Because real progress can be slow. Maybe a story built on tiny wins would make more sense? Kevin Kelly, founder of Wired magazine, termed this protopia: a world that strives to be a little better than the day before. A more realistic take on the ‘sunshine and rainbows’ notion of utopia. Not about flying cars or interplanetary breakthroughs, but small gains that add up. Think of how planting trees in urban spaces can help clean the air and improve mental health, or how opening a youth centre can keep vulnerable young people off the streets. These futures may not be thrilling by sci-fi standards, but they’re more honest about how real change happens. They remind us that imagining better doesn’t always mean imagining bigger.

Futurist Monika Bielskyte, a creative advisor on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, takes the idea of protopia further by reframing it through an intersectional lens. She challenges the dominant aesthetic of futurism—one shaped by white, male, techno-utopian thinking—and instead centres social justice. For her, protopia isn’t about shinier gadgets or space colonies. It’s about plural futures shaped by those who’ve historically been excluded from imagining them. More about cultural repair, and less about technological solutionism.

Dynamic worlds > static worlds

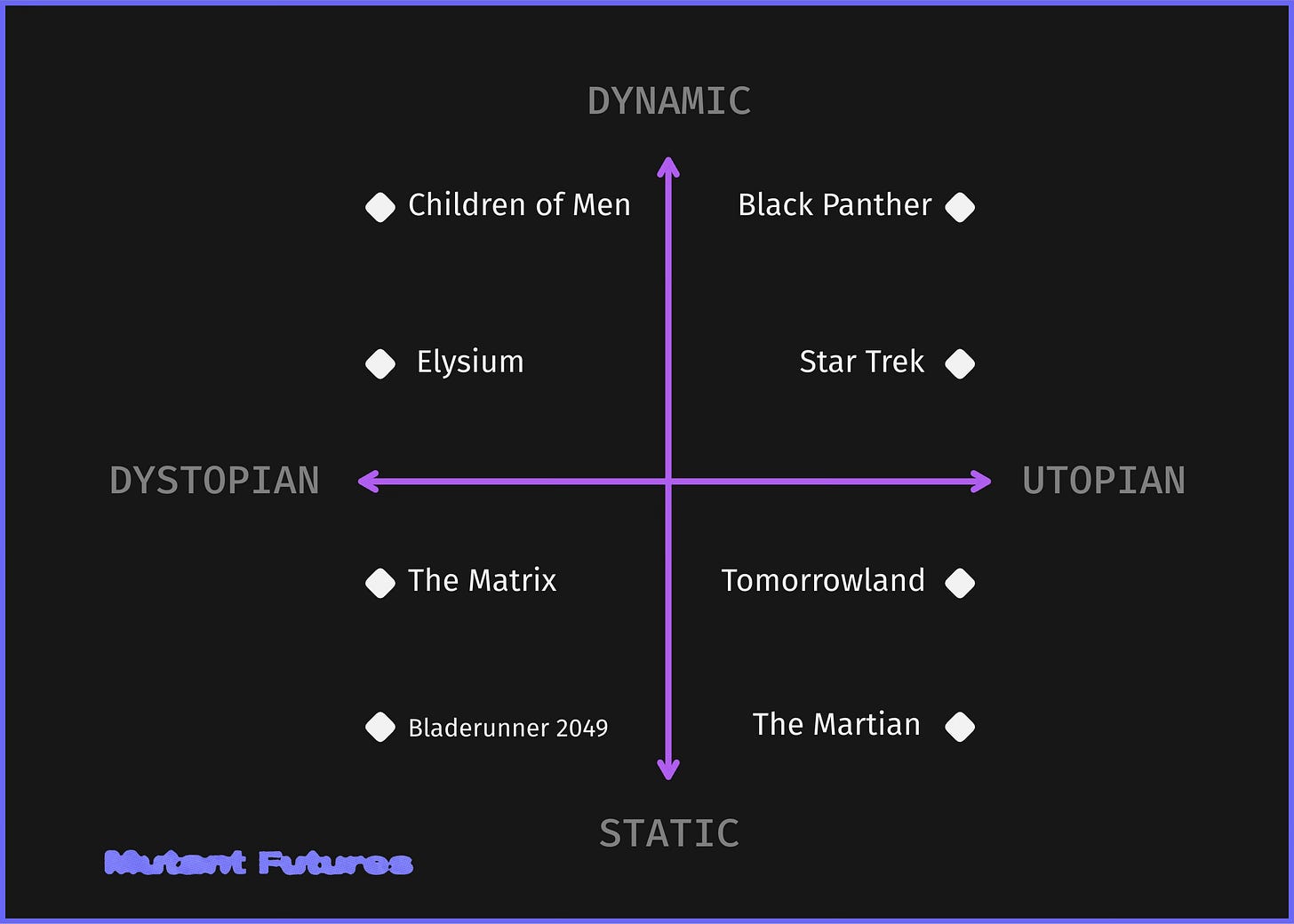

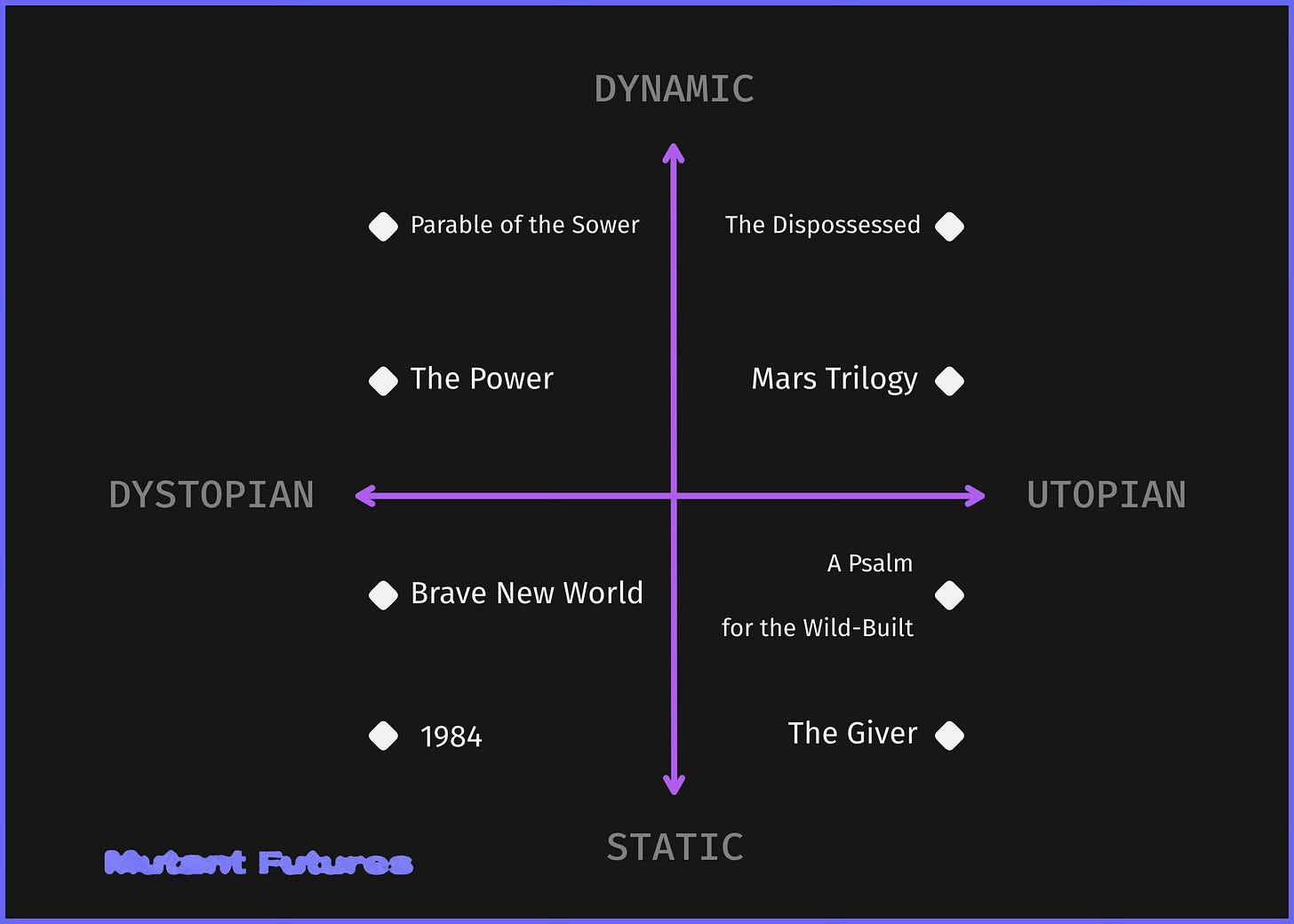

So the utopia-dystopia spectrum tells us about the setting of a story. But it tells us nothing about what kind of evolution takes place in that setting. Does that world evolve, or does it remain stagnant? That’s where a second dimension helps. Because not all speculative fiction is built to expand our sense of possibility. Some fictional worlds, especially those depicted on screen, are just stylish backdrops: heavy on aesthetic, light on intention. So it’s worth asking how dynamic the world-building really is.

That gives us 4 general categories of story:

static dystopias

dynamic dystopias

static utopias

dynamic utopias

Examples from film:

Static Dystopias

Here, the world is dystopian and stays that way. These stories often double down on mood and aesthetics, but offer little sense of revolution:

Blade Runner 2049 is visually stunning, but inert. The story follows K, an artificial human (replicant) assigned to retire his own kind. He uncovers a potential miracle: a replicant born of natural birth. Yet even this revelation doesn’t lead to meaningful change. The world stays bleak, corporatised and indifferent.

The Matrix teases a world of rebellion and awakening, but its sequels fail to build on this. Instead of offering a vision of systemic overhaul, the films settle for spectacle. Overall, the story suggests that even rebellion can be absorbed by the system. But instead of suggesting a way out of this, it leaves us with a circular narrative.

Dynamic Dystopias

These stories depict broken worlds, but show characters actively pushing against them. They’re not pretty, but also not ugly forever. They’re narratives that centre hope and inspire a mindset of resistance:

In Children of Men, society has collapsed under the weight of mass infertility. The world is militarised, broken and stripped of joy. But when a young woman miraculously becomes pregnant, a man determined to protect the last hope of humanity risks everything to get her to safety.

In Elysium, Earth is overpopulated and ravaged by poverty, while the wealthy elite live on a luxury space station. When a radiation-exposed worker breaks into the station to access life-saving technology, he sets off something bigger. What starts as an act of survival sparks a movement for change, to unlock a future where health and dignity aren’t reserved for the few.

Static Utopias

These are well-functioning worlds, where little is questioned or evolved. Conflict is minimal, which can be comforting of course. But without moral movement, these stories can paint a naive picture of the future:

The Martian follows an astronaut stranded on Mars after a mission goes wrong. He survives through scientific wit and determination. The story celebrates human resilience, but its grander themes of NASA optimism and global collaboration remain largely unexamined.

Tomorrowland is about a secret, high-tech city created by scientists and artists to escape the cynicism of the outside world. A disillusioned teen and a former boy genius are recruited to restore the city’s original vision. While the visuals are ambitious, the system itself remains static. It’s more hope-core than anything else.

Dynamic Utopias

These are optimistic worlds that still aspire to be better:

In Black Panther, Wakanda offers a dynamic take on utopia through the lens of afrofuturism. It’s a world rooted in tradition yet open to change. It shows that progress doesn’t mean abandoning identity. While not perfect, its society adapts through debate and growth, not complacency.

Star Trek, specifically VI: The Undiscovered Country, explores the uneasy process of peace-building between enemy civilisations. Set against the backdrop of galactic diplomacy, the film deals with ideological division and rebuilding trust.

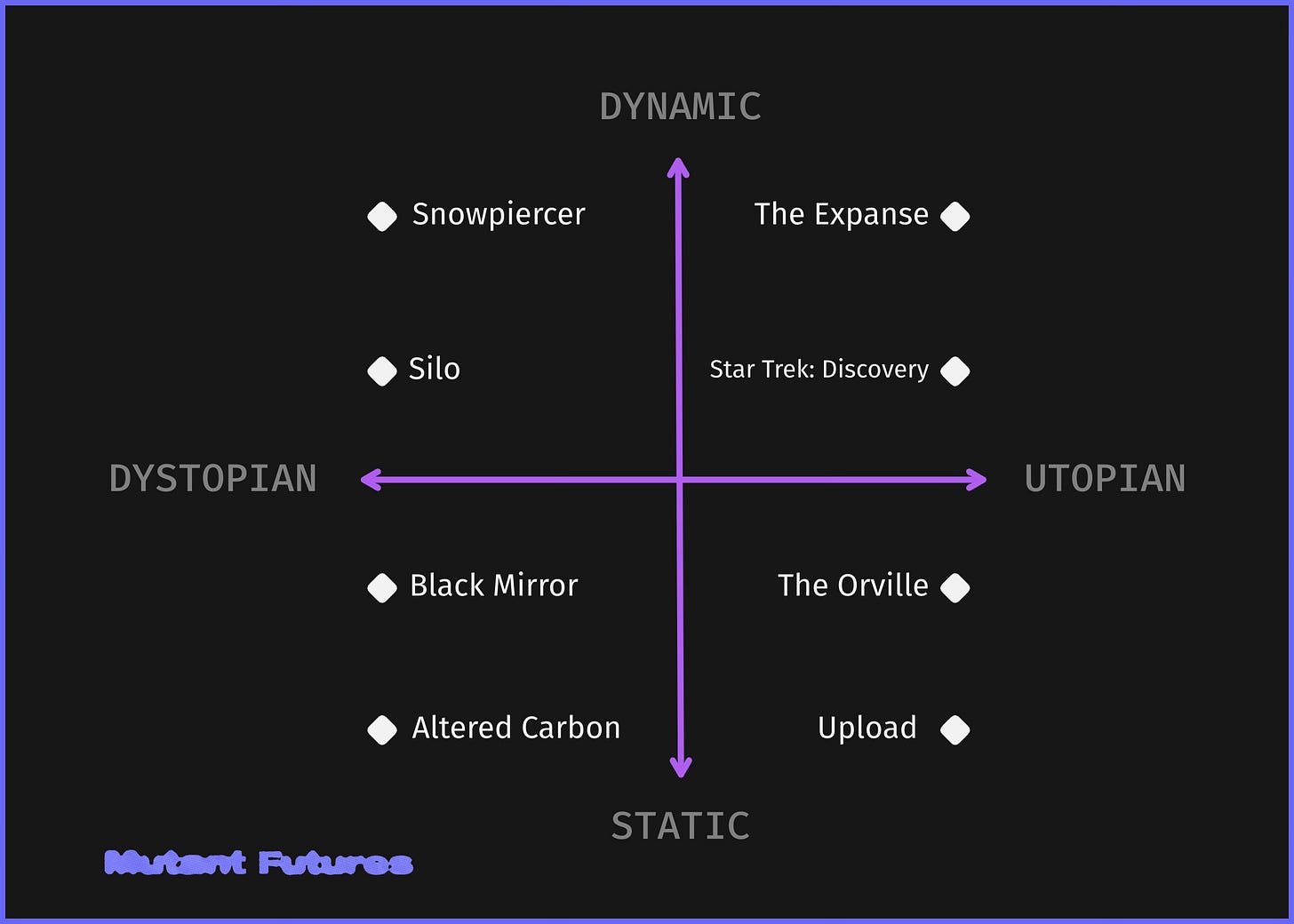

Examples from TV:

The same thinking can be applied to TV shows, though the longer format gives them more room to explore change over time.

Black Mirror is a bit of an anomaly, since it’s an anthology series, so each episode is more like a short film. Most of its episodes involve static world-building, tapping into techno-paranoia or existential dread, with little sense of empowerment. There’s a tendency for TV shows in the sci-fi genre to focus on dystopian worlds, probably because those settings offer more drama.

Utopian series are rarer, and most of them tend to follow the ‘Star Trek’ model: humanity has overcome its problems at home and is now focused on space exploration.

Shows like The Orville, Star Trek: Discovery and The Expanse follow this model. The Expanse is notable for its complex world-building and portrayal of a Solar System in flux. Whether it’s the discovery of alien technology that can help humanity discover new galaxies, or an uprising from marginalised asteroid belt people who form their own union, the series depicts many shifting alliances, uprisings and existential threats.

Upload takes a different approach. It’s a more character-driven story, exploring the evolving concept of a digital afterlife. While it touches on social hierachies and techno-capitalism in a light-hearted way, it’s not as concerned about macro-level shifts like the other shows.

Finally, an honourable mention: Doctor Who. In my view, it doesn’t fit into this 2x2 as neatly as the rest. Its storytelling is more fluid, balancing family-friendly optimism with darker, dystopian elements. The Doctor’s mission to heal and repair, rather than conquer, puts the show in a unique category. While hopefulness is central to the show, it also addresses the failure of hope and the persistence of prejudice, reflecting a humanistic philosophy rooted in empathy and ethical balancing. The series stands for everyday progress, rather than striving for perfection.

Examples from books:

With their depth of world-building and capacity for detail, books can serve as blueprints for imagining better futures. Unlike films or TV shows, books explore not just characters and plot, but the very structures that govern society: laws, institutions, economies, and more. This level of detail allows for a deeper understanding of how change can happen within these systems, offering a more comprehensive vision of a different world.

It’s important to acknowledge classic novels like 1984 and Brave New World. These are foundational texts, no doubt. But their worlds are deeply static. While they are essential for understanding systemic dysfunction, they don’t offer a path forward. That’s why it’s crucial to balance the canon with more empowering stories, like Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, or Naomi Alderman’s The Power. These are thoughtfully constructed stories that can help us imagine how we might repair what’s broken.

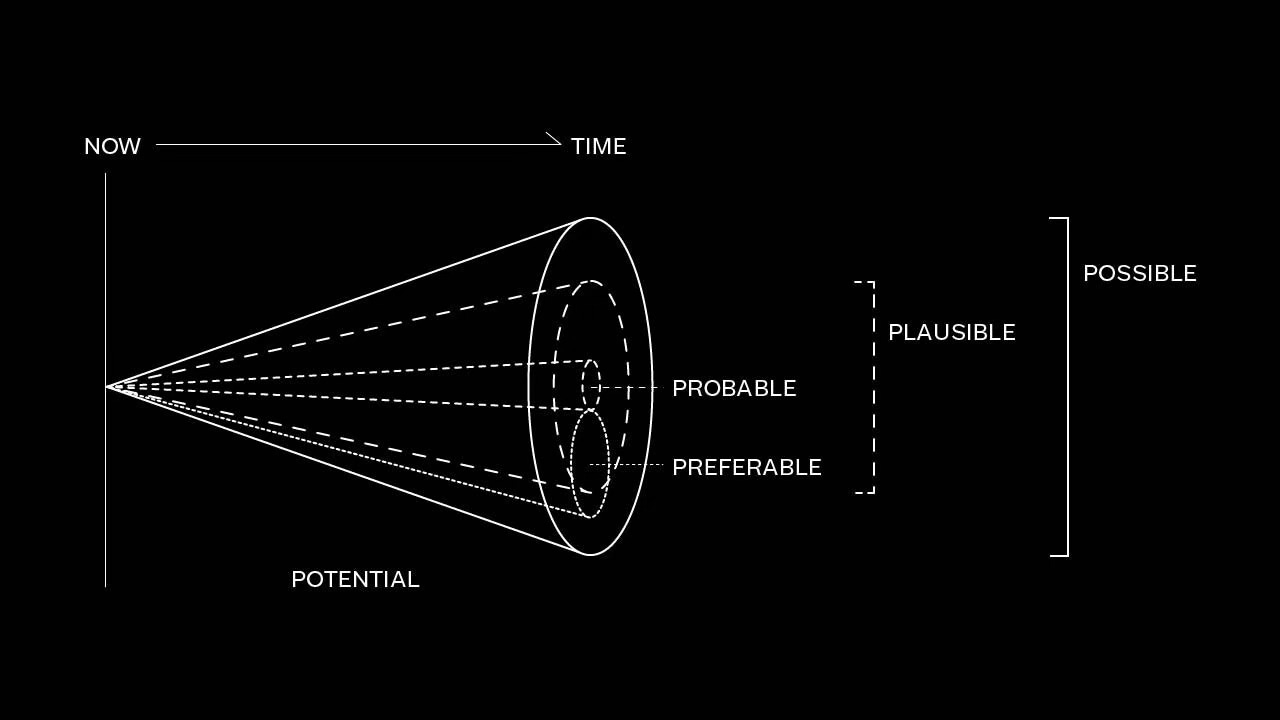

Stories as simulations

Of course, any work of fiction can act as a sandbox for our imagination, regardless of genre. I like to think of it as the original virtual reality: immersing us in a unique environment and someone else’s shoes. But what makes speculative fiction special is that it plays with macro drivers of change. It allows us to investigate the future, by stress-testing various worlds and value systems in the safety of our imagination. Stories become thought experiments, a way of simulating scenarios. And this thinking is actually being put to strategic use: earlier this year, the UK Ministry of Defence was reported to have enlisted sci-fi writers to help with scenario planning. From mass blackouts triggered by cyberattacks to weaponised AI systems undermining national security, their ability to imagine dystopian scenarios can allow policymakers to better prepare for emerging threats. The logic is: if stories can simulate crisis, they can reveal blind spots in the government planning. When done intentionally, speculative fiction can help us investigate the edges of plausibility, by preparing us for a wider range of futures:

Imaginative infrastructure

Fiction becomes dangerous when it falls into a single point of failure; when it frames things like political collapse or techno-tyranny as inevitable. But too much of the same story traps us in a loop of paralysis. We risk normalising a doomer mindset. When our media diets are laced with dysfunction, it’s no surprise that we get future fatigue: a kind of cultural burnout that leaves us unable to imagine or believe in long-term futures. And when we stop believing in the future, we treat the present as whatever. Stories can make us feel seen by portraying a broken system that we can relate to, reflecting our anxieties. But they can also help us strategise a way out of that broken system.

Hope is a muscle. The more we exercise it, the more we empower ourselves, regardless of what’s on the horizon. So let’s focus on better stories, and work that muscle.

Thank you for reading! 💜 If you haven’t subbed already…

SO fascinated to read that the UK Ministry of Defence enlisted Sci-Fi writers with scenario planning! Just loved this - hope IS a muscle.

Absolutely brilliant piece, Philip. I loved how you unpacked the idea of dynamic world-building and the shift away from binary thinking.

Also, to echo your point about the UK Ministry of Defence enlisting sci-fi writers for scenario planning, France has been doing something similar since 2019 with Red Team Défense.

It’s an initiative by the French Ministry of Armed Forces, bringing together science fiction authors, screenwriters, scientific and military experts and together they imagine disruptive future threats. You can even explore some of their scenarios on their website: https://redteamdefense.org/en/home

They’re structured in seasons, just like a TV series :)