Speculative slowness

Going beyond the edge of tomorrow

Welcome to Mutant Futures: a newsletter about culture, futurism and strategy.

The Future of Slowness is a mini-series about infusing a Mediterranean sense of time into Western culture.

In essay #1 (Stuck on fast-forward), I argued that we need slowness more than ever because we’re accelerating beyond what our senses and systems can handle. In #2 (Seeds of slowness), I discussed transformative counter-shifts (cultural trends, design principles and other signals). This is essay #3.

Enjoy!

P

In the last instalment, I discussed real-world developments embodying slow values. But here, we go a step further: what kinds of objects would exist in a world beyond the rush? Objects that can spark conversations about alternative realities. By expressing slow values in some form—a product, a service, an event—we gain a better understanding of what a more desirable existence under capitalism should look and feel like. Because design is, in the words of graphic designer Brian Collins, ‘hope made visible’. It can help bridge where we are with where we want to go. To emancipate slowness, it helps to have concrete reference points. So let’s get into them.

Tech that’s counter-cultural

Consumer tech gets a bad rap for being synonymous with addiction, short attention spans, and many more societal problems. And while that’s undeniable, we shouldn’t ignore the potential for tech, enlightened by human needs, to challenge this narrative and help us make small wins.

As we’ve seen with young people falling in love with old tech, people yearn for simple devices that don’t hijack the tempo of their lives. So why not bring that sensibility into current design? Why only look to the past for those objects? In my view, the shift towards more ‘semi-smart tech’ (as I like to call it) is already underway. Don’t get me wrong, the world doesn’t need more stuff. But new stuff needs to set a better example for respecting our time and attention.

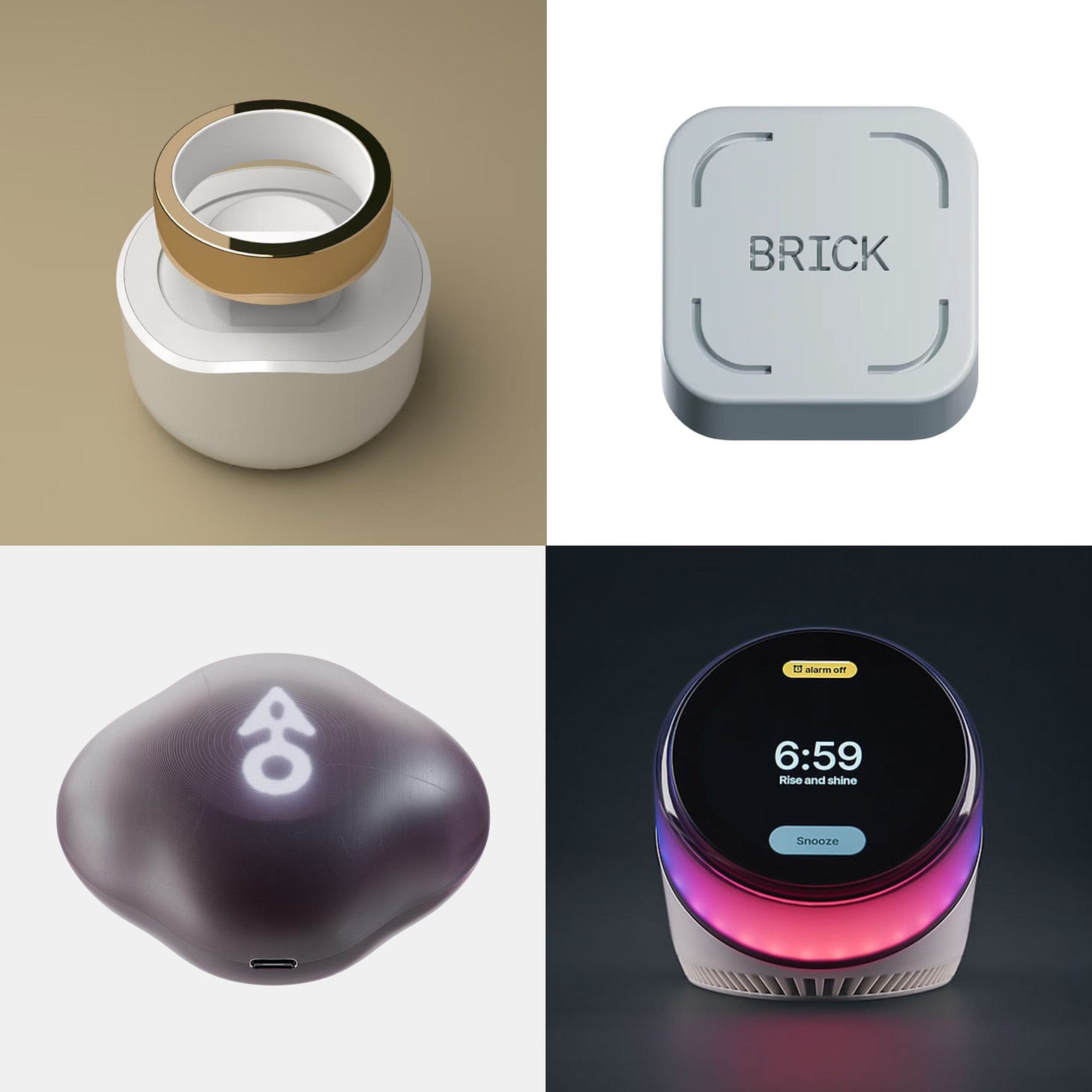

Some physical examples

Here are some objects often marketed as tools for slower living, though they also show how hard it is to escape the cult of speed. Their value lies in what they reveal about contemporary desires and societal constraints, not in the idea that gadgets can produce slower futures. Lifestyle upgrades should not be confused for forces that genuinely alter the pace of daily life. If anything, what they expose is a growing unease with acceleration, rather than a departure from it.

Pulse - this ring emits a vibration at scheduled intervals, to remind the wearer to stay present. What makes it interesting is that it flips the usual logic of wearables: it doesn’t encourage self-optimisation by tracking some biometric, but simply assists with staving off distractions.

Brick - a smart widget that temporarily blocks distracting apps and websites on your smartphone. The idea is that the widget lives somewhere permanently, like on your fridge door. So if you were to leave the house after ‘bricking’ your phone, you’d have to wait until you’re back home to unlock it.

Terra - a device for wandering outdoors without the distraction of your phone. You start with a text-prompt (e.g. ‘Two-hour Marais stroll with patisserie visit’) and it generates a bespoke route using AI. It then guides you along the route with haptic feedback and an arrow interface. The prime use case would obviously be urban exploration abroad, untethered to your maps app. But I can picture devices like Terra resonating with a Tamagotchi-like nostalgia in our everyday lives.

Dreamie - a touch-screen alarm clock that requires no smartphone whatsoever to use it. It doubles up as a bedside lamp and comes with a multitude of features, including nature recordings and breathwork sounds. This is what I mean by ‘semi-smart tech’. I don’t think the slow benefits need further elaboration.

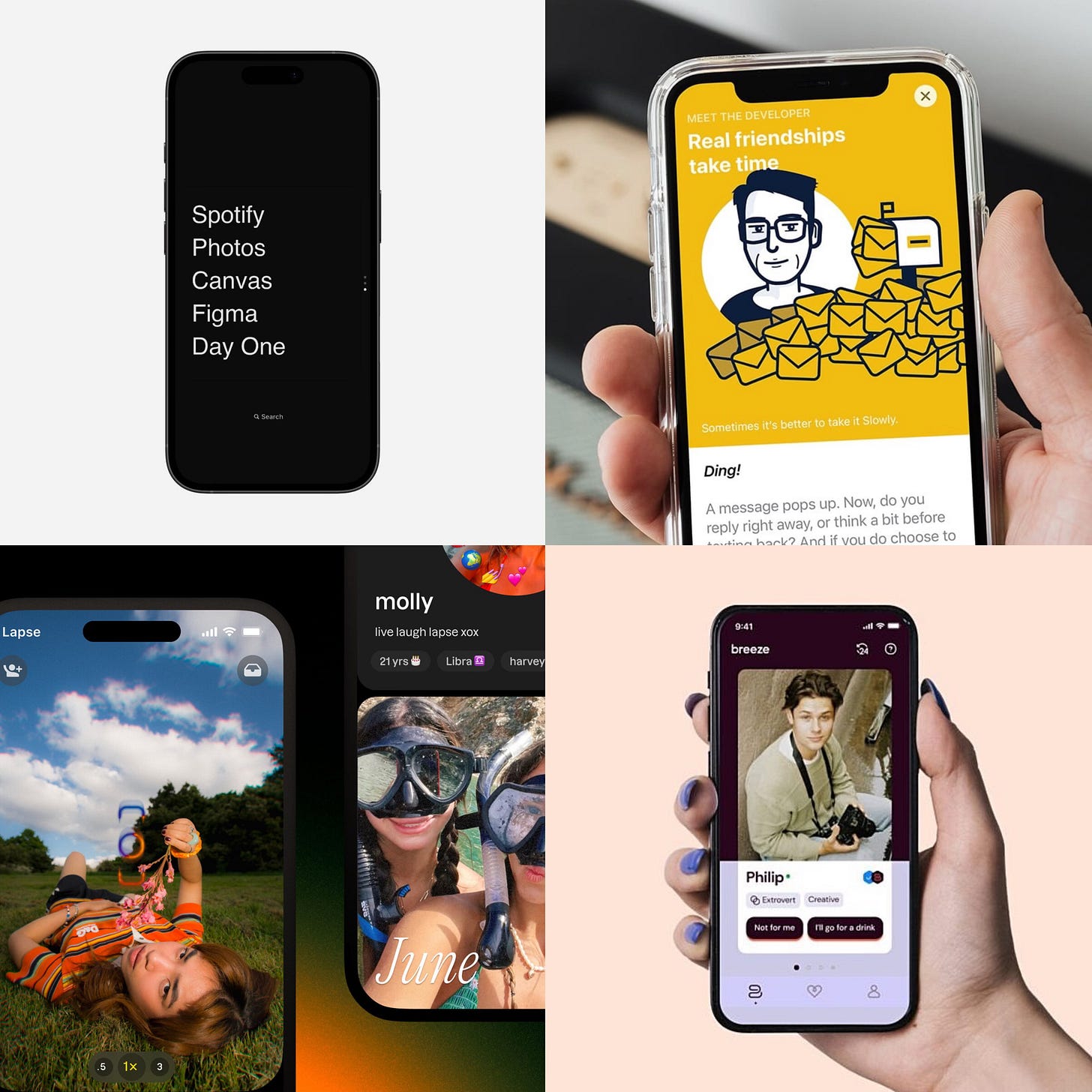

Some digital examples

Apps like the below rely on ‘microboundaries’—small frictions in the user experience to prevent auto-pilot behaviour. But like the physical examples, they’re still embedded in systems designed to hijack your time. They’re useful here to show how app and UX design can interrupt certain compulsive triggers, despite the broader conditions that create those triggers.

Blank - this app strips your home screen of icons, notifications and visual clutter. By minimising the interface, it reframes your device as a functional tool rather than an invitation to scroll. The effect is subtle but helpful.

Slowly - designed to emulate the penpal experience, this app lets you write a letter to someone in another country, and arrives later in their app depending on geographical distance. While there are several apps dedicated to foreign language-learning and multicultural exchange, anticipation built into this one makes each message seem more meaningful and rewarding.

Lapse - an app inspired by the disposable camera: you take pictures, then wait for them to ‘develop’. Photos are only ever shared within your trusted friend group rather than publicly—and there’s no followers. The app seems to have solidified a niche Gen Z following, driven by the intentionality of its delayed gratification concept.

Breeze - a no-swiping dating app that skips the digital chat entirely. Every day you get just a handful of profiles suggested to you, and if you match, the app schedules the date for you. While some may find the concept a little too ‘blind’, the idea is to simplify endless choice and respect people’s time (i.e. no ghosting). Interestingly, the app describes itself as ‘slow dating’ (I can vouch for this).

Dreaming out loud

As I said at the beginning, when we have alternative realities to reference, our understanding of what’s possible expands. To quote design futurists Anthony Dunne & Fiona Raby in Speculative Everything (2013):

As we rapidly move toward a monoculture that makes imagining genuine alternatives almost impossible, we need to experiment with ways of developing new and distinctive worldviews…It is our hope that speculating through design will allow us to develop alternative social imaginaries that open new perspectives on the challenges facing us.

The point here is not to create blueprints, but to test assumptions about what slower futures might require from our environment. Not predictions, but provocations. Thought experiments for probing the limits and tensions of the current system.

Tech-facilitated slowness and retrofitted rituals

A key curiosity driving my research on slowness has been how to reclaim it in megacities. The reality is that more than 50% of the global population lives in cities, and is expected to be nearly 70% by 2050. With that in mind, what if we used tech to take the edge off the less glamorous parts of urban life? Imagine having a prettier, more calming view out of your window than a construction site on a grey day in London. Digital windows and blue sky ceiling panels can do that. Of course we’d all prefer real views and nice weather, but interior changes like these at work and home could help reduce cognitive fatigue and things like seasonal affective disorder. Driven by the benefits of biophilic design, this logic could also apply to virtual spaces. Imagine if your line manager catch-up was a walking meeting in VR that leveraged the stress-relieving effects of forest bathing? We’ve cracked how to walk on the spot in VR, so why not spice things up at the office?

Also, what if we applied new tech to social rituals? Inspired by Mediterranean culture, one of the easiest ways we could encourage more slowness is through more shared meals. Even socially active urbanites sometimes eat alone. But what if we dined with AR holograms (e.g. of family members who live abroad) using smart glasses? A more meaningful way to have dinner alone than letting a screen keep you company.

Another idea: what if we normalised the afternoon siesta at work, and took naps at lunchtime? While sleeping pods in the office are more associated with corporate workplaces requiring all-nighters, the workplace siesta (which is not a new idea) would almost certainly bring back some slowness, and rest, to our everyday lives.

Radical curation / curation-as-a-service

I think the future of media consumption is radical curation. When there’s too much of everything, sophisticated curation could be the way out. The world is already full of curators: DJs, link aggregators, cultural commentators, salon organisers. Why not take it further? Personalised curation-as-a-service could combine human taste with machine precision. Here’s how it might work for film:

Your taste profile and selection criteria (whether you choose films by critical acclaim, director, actors, premise etc) are analysed to build a custom recommendation algorithm.

A human curator then verifies the algorithmic picks and narrows them down to say, 5 films a month. And because this service is platform-agnostic (i.e. run separately to the streaming platforms), there’s no agenda to keep you watching a catalogue of mostly trash. Think JustWatch but for taste.

This can save time while broadening your palette, breaking you out of feedback loops of familiarity, nostalgia or irrelevant word-of-mouth.

This logic could eventually be absorbed by quality-focused streaming platforms. The appeal of cinemas, aside from being phone-free sanctuaries, is their modest selection. A future MUBI (or other company) might not show you an entire library, but a set menu of five films that day. Enough variety without decision paralysis. This could free up time and headspace for more thoughtful cultural consumption.

Repair service ubiquity

Finally, and this goes back to the repairability point I made in the last essay, normalising repair services at big brands could stretch out cycles of consumption. This could unlock more time for people, who’d otherwise be spending it shopping for a replacement item, or poring over online reviews. Clothing brands like Patagonia and Nudie Jeans already offer this as a standard complimentary service, so the economics of it is tested. The case for big brands to embrace repair services is not implausible, especially the ones on the pricier side, like Apple, Sonos and Dyson.

But also, it would be groundbreaking to see this adopted at high-churn brands like Adidas and Uniqlo. In a world drowning in stuff, repairing and renewing the old stuff offers untapped value, and the shift towards a pro-repair culture is already underway, with repair cafés on the rise in big cities and the right to repair gradually becoming recognised by forward-thinking legislatures. As new products get less exciting and more about upgrading for status, durability becomes the only thing that actually feels worth paying for. And with buy-now-pay-later easing bigger upfront costs, the idea of buying something more durable and premium starts making sense to more people than just the eco-crowd and well-off consumers.

Keeping it real

In closing, there is value to radical daydreaming, if only to escape our assumptions about the future. However, no object or interface can deliver slowness on its own. We still have to reckon with the political, economic and infrastructural conditions that determine how time is organised. Slow design only means something when it intersects with those conditions, rather than hovering above them as abstraction. Most of us remain caught in feedback loops of dopamine and convenience, which makes the pursuit of slowness feel both necessary and difficult.

So in the next and final essay of the series, I’ll be going back to a more grounded discussion on economic realities, convenience culture and the trappings of ambition.

See you there.

I loved reading this! Also reminded me of the new Fairphone with the Dumb-Phone Button: https://www.fairphone.com/en/2025/07/03/fairphone-moments-switch-to-distraction-free-digital-minimalism/